Live, Laugh, Leave: Has Sweden adopted the pantsuit model of migration?

Are their recent changes merely cosmetic or do they herald something real? And how have things progressed in Denmark, Italy, Britain and Europe more widely?

Last year I wrote on what a respectability cascade on immigration policy might look like. A new mainstream consensus that the mass, unselective immigration of the last two decades had to end. Respectable common sense, ‘difficult but necessary’, no pantomime villains dreaming about sending migrants to Rwanda. Instead, restrictive policies being competently and quietly enacted by the political centre, and the issue thus becoming somewhat depoliticised.

Following the recent example of others on X, we could call this the pantsuit model of migration management, named for its emblematic politically mainstream and technocratic female implementers. The pantsuiters implement restrictive policies not out of any particular dedication to the ideas themselves, but simply because they are expected to as part of their centrist political platform. Unlike populist right figures, their career incentives and personal characters lead them to want to achieve results while maintaining respectability: avoiding, not courting, controversy.

The crucial question is whether the pantsuit model does represent a change in the mainstream stance on migration policy, or whether it is just a slightly less extreme and more orderly version of the system we already have. If the former, the issue’s effective handling and depoliticisation would be a positive for all except for pro-migration ideologues and useless anti-migration grifters, both of whoms’ careers I would be eminently willing to sacrifice. But if the latter, then it would be a largely symbolic and deceptive sop by the mainstream to stop the bleed of their electorate to the populist right, and one that in the long term would actually prevent the problem being tackled effectively.

It is this question I will be looking at, in Sweden and the rest of Europe.

Denmark, a recap

Denmark is the most longstanding example of the pantsuit model in action, as I recently wrote about. The centre-left Social Democrats eventually (in 2019) adopted the restrictive asylum stance first advocated decades earlier by the populist right, primarily the Danish People’s Party (DPP). Their current PM, Mette Frederiksen, is an emblematic pantsuiter, who has stated, among other things, that her government’s goal was ‘zero asylum seekers’.

As I wrote, ‘restrictive’ is relative: Denmark is comparatively restrictive compared to the rest of Western Europe, rather than in an absolute sense. It is managing to avoid the worst pathologies of mass migration but not the overall trend.

Their brief history is as follows. In the 2001 Danish elections the Social Democrats had their 76-year election winning streak broken by a coalition of right-wing parties, including the DPP, in an election where immigration played a central role. In the following two decades the DPP managed to get many of its policy demands on immigration enacted via its parliamentary support for the right-wing governing coalitions which ruled for most of this period, keeping the hitherto dominant Social Democrats mostly out of power. This resulted in Denmark developing Western Europe’s strictest immigration policies.

The most significant victory for the DPP though, I would argue, came in 2019, when the Social Democrats returned to power on a distinctly DPP-like platform, exemplified by the statements of their aforementioned new PM Mette Frederiksen. Their stance has so far been maintained, while concurrently the DPP and the populist right in general have declined as a force in Danish politics since their electoral peak in 2015.

In their success therefore the DPP undermined much of the reason for their own existence. Real victory comes when your policies are no longer even seen as ‘political’ at all, which to a significant extent is what has happened in Denmark. The populist right torch is now predominantly carried by a different party, the Denmark Democrats, but absent a breakdown in the new consensus on migration, it seems unlikely that they will ever reach the electoral heights that the DPP did.

The pantsuit model comes to Sweden

Sweden of course has a reputation as being a country exceedingly open to migration, especially to refugees from the Middle East. For the past few decades this reputation has indeed been earned: Sweden has frequently been Europe’s highest per capita recipient of asylum seekers. As readers will know, these policies have led to Sweden shooting up various other international rankings such as gun homicide rates, which has been amply documented elsewhere.

In early August of this year however Minister for Migration (and pantsuiter) Maria Malmer Stenergard of the Moderate Party announced that more people were now leaving Sweden than arriving and that asylum applications were the lowest since 1997. This was claimed to be as a result of the government’s migration policy ‘paradigm shift’ since 2023 involving stricter asylum, labour migration and family reunification requirements.

The political process that brought this paradigm shift about was similar to what happened in Denmark, although while there the political mainstream was willing to work with the populist right from the early 2000s, in Sweden they maintained a cordon sanitaire until 2019. As in Denmark, migration was forced onto the political agenda by an initially minor populist right party: the Sweden Democrats (SD). They had been steadily gaining support for two decades concurrently with Sweden’s migration problems: 20 seats in 2010 (6th largest party), 49 in 2014 (3rd largest party), 62 in 2018 (3rd largest party), and 73 in 2022 (2nd largest party).

The cordon sanitaire broke down in 2019 after the Moderates and Christian Democrats agreed to work with the SD, and after their success in the September 2022 election, the SD formed a governing coalition with these two parties and the Liberals. The Tidö Agreement that followed in October 2022, setting out the structure of the new government, specified the planned paradigm shift on migration. Among other things, this specified that asylum would now be for temporary protection and only at the minimum level required by Sweden’s legal obligations, and that tighter labour and family migration requirements would be introduced.

In many ways, this appears to be the direct application of the Danish model to Sweden, down to the terminology used (‘paradigm shift’) and specific policy details such as the increase in the time one must be resident in Sweden to apply for citizenship from five to eight years (matching the Danish requirement). As in Denmark twenty years earlier, it is being implemented under a broad right-wing coalition with significant populist right influence, but not led by them (Sweden’s PM is Ulf Kristersson of the Moderate Party).

The paradigm shift attracted little attention in the international press until Malmer Stenergard’s August announcement where she called for ‘sustainable immigration’ (good term) and that restrictions were needed to ‘reduce social exclusion’. So far, so pantsuit.

Following on from this, early in September, the Swedish government announced it was increasing the benefit paid to migrants who agree to go home from 10,000 to 350,000 krona (from about £700 to about £25,000). The SD’s immigration spokesman Ludvig Aspling commented “We’re basically just trying to help people live their best lives.” Could there be anything more pantsuit than that? Might I suggest “Live, Laugh, Leave.”

Is the paradigm shift in Sweden real?

In Denmark, as I described, their migration model is genuinely restrictionist, at least relative to the Western European norm. Has the paradigm shift meant the same thing for Sweden?

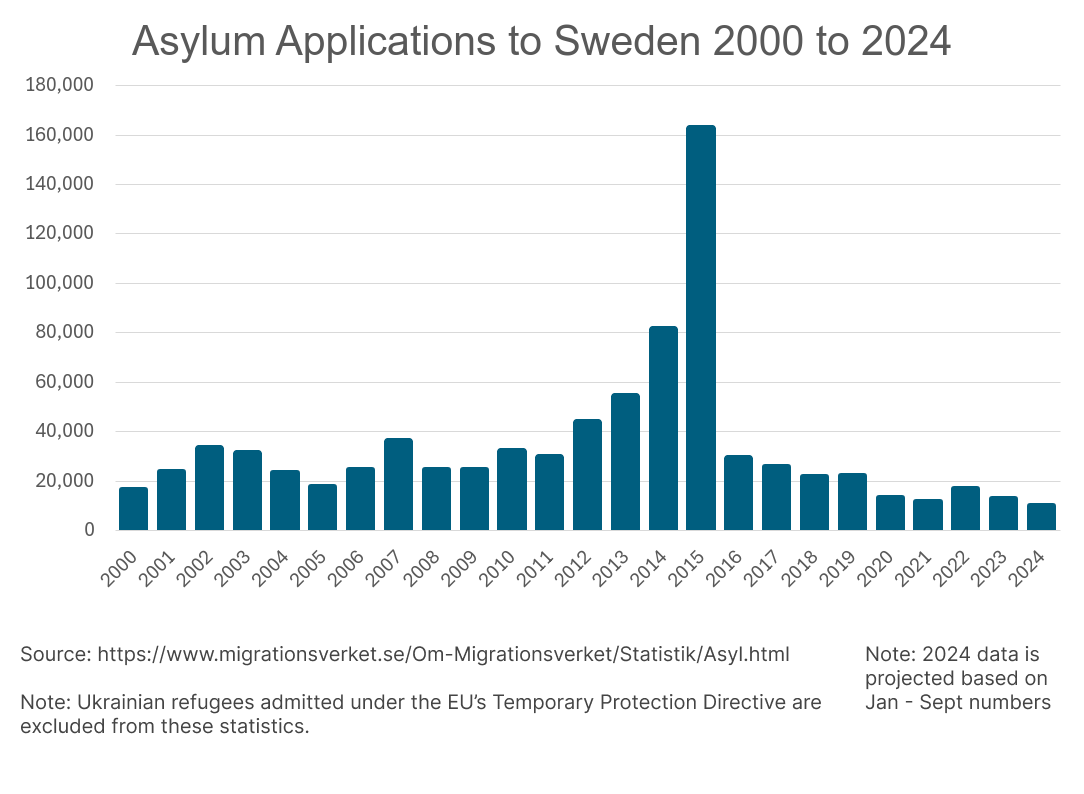

Maria Malmer Stenergard claimed that Sweden had the lowest rate of asylum applications since 1997, and this does indeed seem to be the case, or at least since the year 2000 where I can find data from.

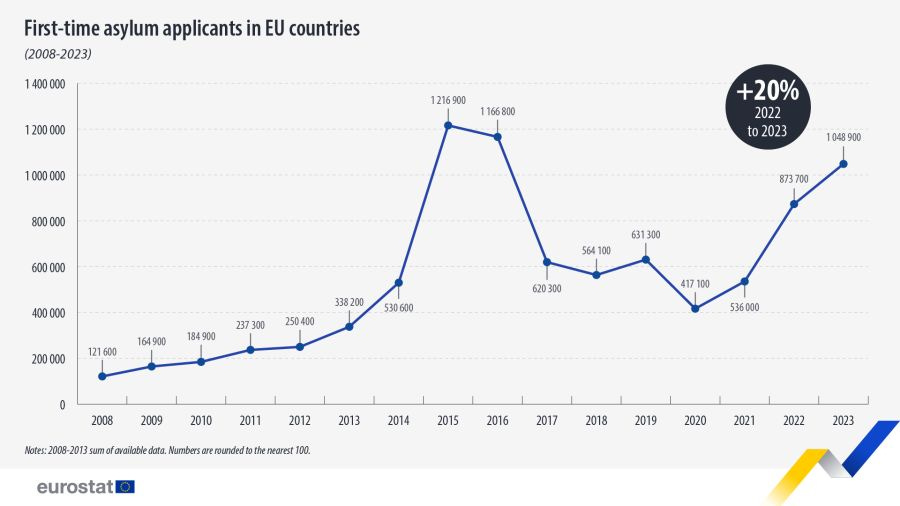

This decrease is specific to Sweden; it is not a result of decreasing asylum rates in general, as the EU overall has seen a sharp rise in asylum applications over the last few years, almost reaching the peak of 2015 and the Syrian civil war.

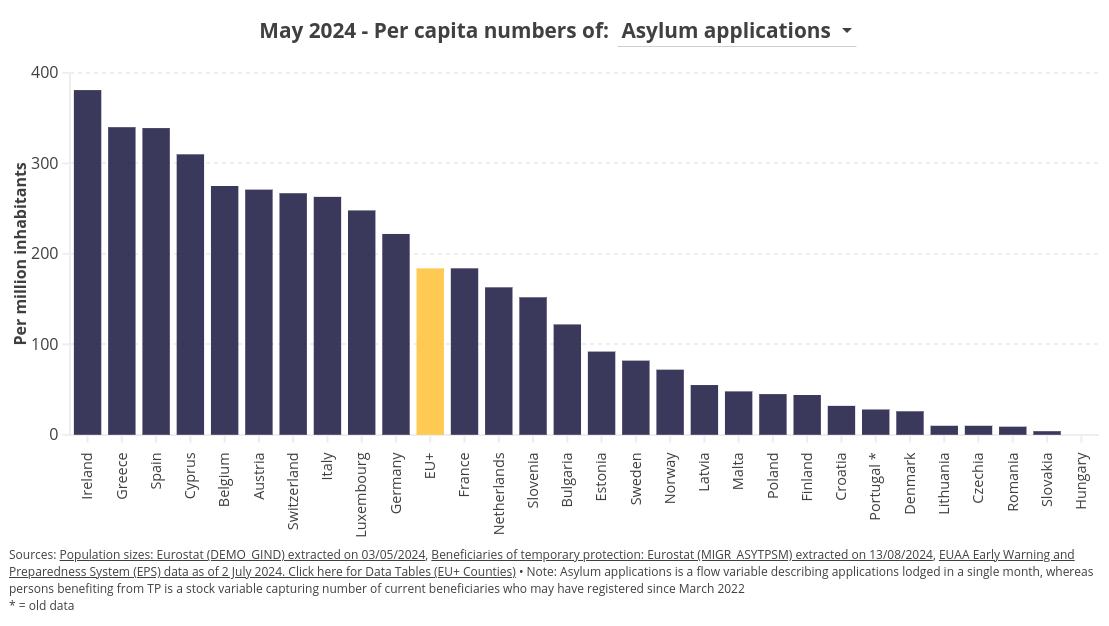

In fact as of May this year Sweden has one of the lowest per capita rates of asylum applications in Western Europe.

Therefore we can say that the new Swedish government has indeed been quite successful at deterring asylum seekers. As an aside, this is a clear counter to the claims of some in Britain that there is no evidence that government policy acts as a deterrent, is false. Here it is.

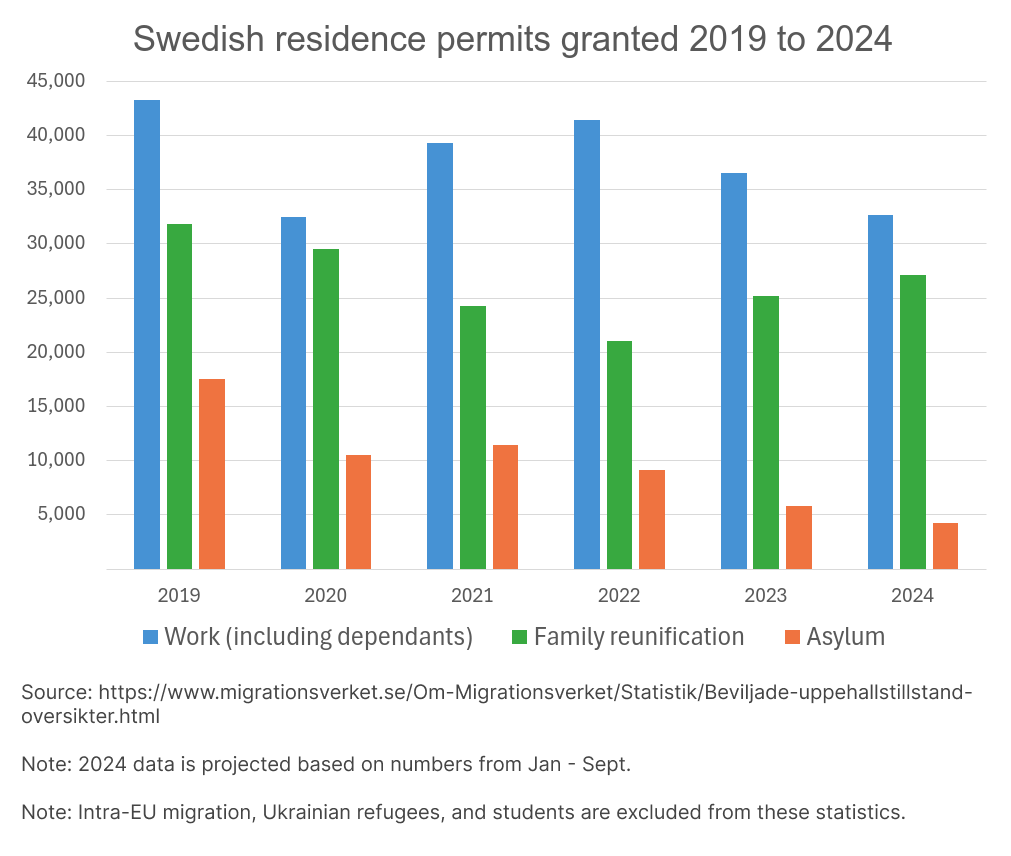

Malmer Stenergard also claimed that asylum related residence permits continue to decrease, and this too is indeed reflected in the statistics, with numbers showing a clear decline since 2019. For comparison, 2023’s Swedish asylum permits numbers (scaled by population) were around half of those given in Britain in the same year (62,336).

In this data though we can see the limitations of Sweden’s new restrictionism. Family reunification, likely a result of previous asylum grants, has not seen any significant decrease. Although as they are to some extent a consequence of asylum numbers, they will presumably begin to fall in future.

Non-EU labour migration also has not significantly decreased. Though unlike in many other countries recently, e.g. Britain’s post-Covid ‘Boris-wave’ of low paid care worker migration (and their dependants), it has not increased either. Looking into the details of who gets these visas, the majority of permits here are for agricultural workers (which are presumably temporary) or for various categories of engineer. There seems to be little low paid long term labour migration. Overall, to take 2023 as an example, in Sweden there 36,514 work and dependant visas granted. In Britain there were 616,371 such visas granted, nearly three times as many as a proportion of the population, and largely as a result of the massive expansion in care worker visas.

Overall then we can say that Sweden has had genuine success in reducing its asylum numbers, moving from being Europe’s most charitable country to one of its more restrictionist ones, though not, yet, to the extent of Denmark. Regarding other forms of migration, things have not changed much in either direction. The Sweden-Democrats infused government is at this point around two years old, so we shall see in the next few years, and especially once the left returns to power, whether the pantsuit migration model has really taken hold or not.

Update 9th Oct: in the original article I reported but did not discuss Malmer Stenergard’s additional claim that more people were now leaving Sweden than arriving. However thanks to Stefan Schubert, it’s worth pointing out this is likely not the case and is the result of a lag in the tax authority’s de-registering of citizens leaving the country.

The pantsuit model outside of Scandinavia

So the pantsuit model has, to some extent, come to Sweden, but what of the rest of Europe? I will not be looking deeply into what has been achieved substantively here, but at least in terms of rhetoric, there are signs.

Many have used Giorgia Meloni as an example, citing her government’s success in cutting illegal immigration arrivals by sea by 60% via various measures including signing deals with North African countries to stop departures, increasing deportations of those with failed claims, and introducing processing of claims in Albania.

Initially I resisted this categorisation: despite Meloni’s admitted fondness for a pantsuit she is an avowedly right wing figure historically happy to court controversy. Early commentary after her election in 2022 focused on her political origins in the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement and generally tended towards the well worn ‘rise of the far right’ narrative.

But mainstream opinion had softened by spring this year, with Meloni forming a kind of informal alliance with the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen: working together to make deals with North African countries to limit illegal immigration. Meloni achieved her own normalisation (pantsuitification?) by acceding to some things EU elites really care about, in Von der Leyen’s words, being "pro-European, pro-Ukraine and pro-rule of law." This is in notable contrast to figures like Le Pen or Orban, and allowed her space to get things done on illegal immigration.

More recently though, as described in that article, Meloni has moved back to a eurosceptic position and ended the alliance with Von der Leyen. Her normalisation has not been completely undone though: Kier Starmer, a male pantsuiter if ever there was one, has “commended Italy's remarkable progress on irregular migration”, and Yvette Cooper is looking on for tips.

Michel Barnier, France’s new Prime Minister, is another (partial) pantsuit example. Too conservative to be a true pantsuiter, he however does have their tendency of being a dyed in the wool figure of the establishment. Lauded by FBPE types during the Brexit negotiations for fitting the image of a respectable, sensible Eurocrat, he did also, awkwardly, call for a moratorium on non-European immigration in 2021.

There are even some signs that the model may be sprouting in Germany, which has just reimposed border controls, justified by its own pantsuiter, interior minister Nancy Faeser of the SPD, in order to ‘curb migration and protect against Islamist terrorism and serious crime’. Germany is always likely to be a laggard on this issue, but if respectable opinion in Europe as a whole shifts sufficiently, I am pretty confident that German political elites too would fall into line. It would be Für Europa after all.

As for Britain, we do have our own pantsuiter representative if only in terms of style and rhetoric, Home Secretary Yvette Cooper. Though she technically seems to favour the ‘dress suit’, if such a term exists, over the pantsuit, she did recently announce a crackdown on illegal migration and to increase deportations.

In terms of practical outcomes though I have very little faith in the Labour Party on this issue. With the Tories having been utterly discredited and the right-wing voter base being split between them and Reform, Labour have little political incentive, and certainly no ideological appetite to tackle the issue in any substantive way. In Denmark, Sweden and Italy, right wing populist parties had significant influence on actual policy. In Britain this has not yet happened, though it is possible depending on who wins the Tory leadership election (Jenrick currently looking the most positive, though I have reservations), or if Reform somehow manage to replace the Tories.

The overall lesson then is that the pantsuiters will do what they must to stay in power and stay respectable. It is up to those with deeper commitments to determine what those requirements will be.

Other articles you may like…

Getting to Denmark on immigration: how to speak softly and carry a big stick

By the end of their 14 years of rule over Britain, the Tories found themselves in the worst of all possible worlds on immigration, one that neither pleased their supporters nor mollified their enemies. They had presided over unprecedented and ever increasing numbers

Imagining a respectability cascade on immigration in Britain

This article originally appeared in The Critic.

Great article. Nice to learn what will happen in Ireland in 25 years time (eyeroll emoji)