Narendra Modi and the BJP in India are the most successful right-wing movement of the 21st century

A 100 year old Hindu nationalist project is coming to fruition

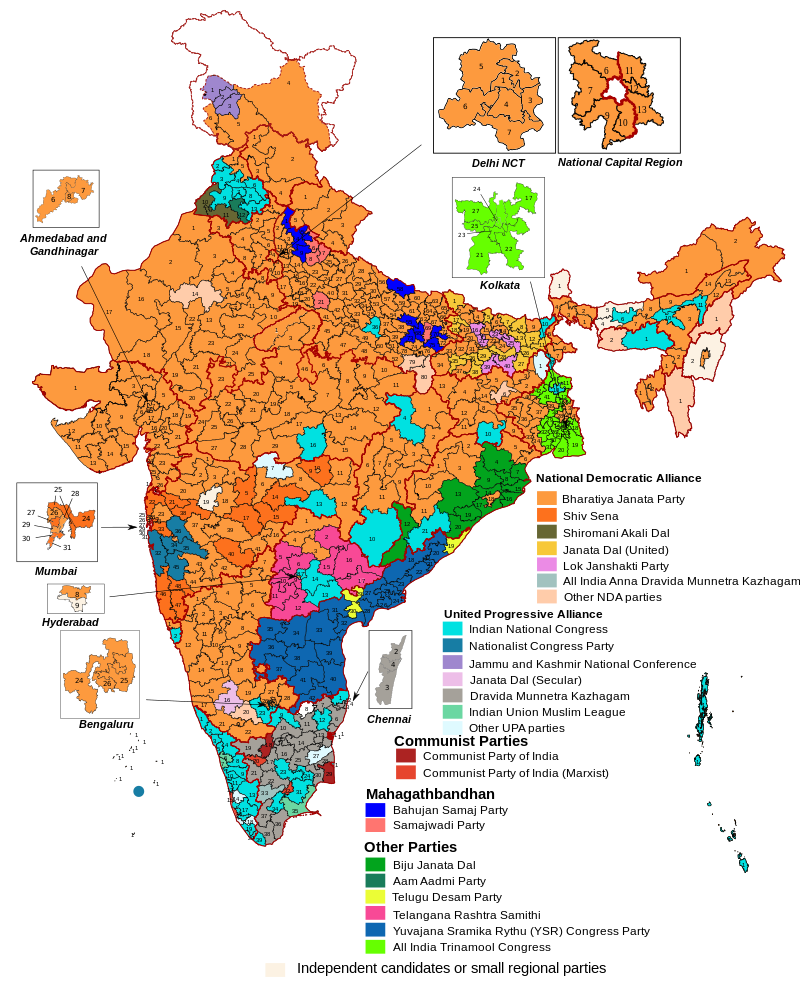

The 2024 Indian general election is currently taking place (it lasts over a month and the results are released on the 4th of June) and will almost certainly be won again by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led by Narendra Modi, and will return him for a third term as Prime Minister. From talking to people in my life who I might expect to be interested in such things, and reading the Western press who see everything through a parochial lens, I generally detect a remarkable ignorance about what Modi and the BJP really represent. What they represent is the most successful right-wing movement of the 21st century, and perhaps of the entire post-WW2 world.

What the BJP and Modi have managed to achieve since the 90s is to overturn a secular socialist governing class and official national philosophy which had been entrenched since independence in 1947, and transform the country in line with their vision of a Hindu Rashtra, or Hindu state. Modi’s image is of an ascetic priest-like figure presiding over this transformation as well as a political leader: he abandoned his brief arranged marriage, unconsummated, aged 18, and since then has dedicated his life to the Hindu nationalist project.

The success of this project and his role in it is symbolised by his personal consecration of the Ram Mandir (Rama Temple) in Ayodhya earlier this year. The construction of this temple was the culmination of a decades or even centuries-long Hindu nationalist project to build a Hindu temple at the supposed site of the birthplace of Rama and to destroy the Mughal-constructed mosque that had stood on the site for nearly 500 years.

The progress of the project is matched that of the BJP itself. In the early 80s the temple construction movement was appeased but not celebrated by the secular Congress government, meanwhile the BJP was only a minor party. Both grew in influence over the decade, and in 1992 a Hindu nationalist rally organised partly by the BJP managed to overwhelm security forces and illegally demolish the mosque. The investigation into these events was intended to last 3 months but dragged on for 16 years; in the meantime the BJP had become one of the two main parties in India and had won three elections, though Congress was still competitive, winning in 2004 and 2009. Legal cases against those held responsible by the investigation lasted until 2020, ending with all being acquitted, and in 2019 the supreme court ruled that a Hindu temple could be built on the site; meanwhile the BJP under Modi had taken power in 2014. In January 2024, Modi opened the temple accompanied by a celebrity audience, as a public holiday was declared in much of the country. Basically, the movement won.

The opening of the temple at Ayoda is just one example of the implementation of Hindu nationalism: the BJP also revoked the special status of Muslim majority Kashmir, passed a citizenship law favouring non-Muslims, and are pushing to make Hindi the dominant language. At the same time, Modi has presided over an economic boom which is looking to finally, after decades of unimpressive performance, end the association of India with extreme poverty and make the country a great power.

A brief history of Hindu nationalism: the RSS, the BJP and Modi

By the early 20th century, British India was awash with various nationalist movements. The one best known in the West today is the secular and socialist Indian National Congress, or simply ‘Congress’. This spearheaded the independence movement under Gandhi, and then dominated Indian politics from independence until the 90s under the Nehru–Gandhi family who still control it it to this day. Also well known is the Muslim League which drove partition and the creation of Pakistan. Less well known outside of India is the Hindu nationalist organisation the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (National Volunteer Organisation), or RSS, founded in 1925 and inspired by the concept of Hindutva, best translated as ‘Hinduness’. The RSS was not explicitly political, its goals were more around strengthening the Hindu community with the eventual goal of establishing a ‘Hindu Rashtra’ or Hindu nation. It did not join the independence movement, being more concerned with strengthening Hindu identity, and with Muslims as a greater threat than British rule.

The RSS grew over the next few decades, though never taking part in the independence movement. It was one of its members (or ex members depending on who you ask), Nathuram Godse, who assassinated Gandhi in 1948 on the grounds that he had betrayed India’s Hindus to the demands of Pakistan and Muslims during partition. In the aftermath of the assassination the RSS was banned for a year. This led to a realisation among its leadership that it needed to be involved in politics, and the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) (a precursor to today’s BJP) was founded in 1951, though it and its successors remained a minor force in Indian politics for the next four decades.

During these four decades, India remained dominated by Congress under the Nehru-Gandhi family, remaining an officially secular Gandhian socialist economy, and generally underperforming (described by phrases like the ‘licence raj’ or ‘Hindu rate of growth’). The BJS and other Hindu nationalist parties mostly remained minor forces, though they combined to defeat Congress’s Indira Gandhi in the aftermath of the disastrous Emergency, ruling from 1977 until 1980. During this period the RSS continued its activities, though its reputation remained tarred by its association with Gandhi’s assassin Godse. However like the Hindu nationalist political parties, its resistance to the Emergency gave it a newfound legitimacy.

This Gandhian socialist world was the world which Narendra Modi grew up in. He was born in 1950 in a small town in Gujarat to a father who sold tea on a train station platform. He joined his local RSS chapter as a boy and became highly involved with them. He was married at 18, but shortly abandoned his wife to spend two years travelling across India to various different ashrams and working in his uncle’s canteen in Ahmedabad. In 1971 he became a campaigner for the RSS in Gujarat, where he worked for several years, being active in their anti-Emergency actions.

By the 80s, the BJS had been reformulated as the BJP, and Modi was assigned to them, and was elected organising secretary of the BJP's Gujarat unit in 1987. He rose within the party and moved to Delhi in 1995 and became general secretary in 1998. He was selected as a replacement for the Chief Minister of Gujarat in 2001, a position he held until 2014. In this period he became notorious internationally for his response to the 2002 Gujarat riots where he was accused of condoning violence against Muslims. Until the early 2010s he was banned from Britain, the EU and the US. These events only helped him in India though, he resigned in response to the accusations, ran for chief minister again, and won with an increased majority in December 2002.

Modi remained chief minister of Gujarat until 2014, becoming identified with the success of the ‘Gujurat model of development’ relative to the rest of India. He was then named candidate for Prime Minister in the 2014 election, won it with a large majority, and won again in 2019 with an increased one.

How the BJP and Modi took over India: by making people feel rich and making them feel seen

Clearly, there has long been a significant Hindu nationalist constituency in India. However, the earlier incarnations of the BJP were closely associated with high caste Hindus, which limited its appeal. As Christophe Jaffrelot describes in Modi’s India, one innovation of the Modi-era BJP was to make Hindu nationalism populist and therefore attract a more socioeconomically diverse voter base including lower castes. This has also been done via extensive social welfare programmes. In many ways, for example the breaking down of caste politics, the imposition of uniform marriage legislation, and the attempt to make Hindi the national language, India is going through the nation building process that European countries went through in the 19th century. You can therefore see analogies to the BJP in things like Disraeli’s one-nation conservatism, or in Bismarck’s conservative welfare state.

A second innovation was to embrace economic liberalisation and globalisation and gain the support of the business classes. Historically the BJP had advocated national self sufficiency and protectionism, but Modi’s Gujarat model changed this. In reality this is more a case of continuing what was already happening than any particular economic genius of their own. Gujarat was already economically successful when Modi took over, and nationally he is lucky to have risen to power at a time when the Indian economic boom was already happening, ushered in by others such as the economics PhD holder Prime Minister from 2004 until 2014 Manmohan Singh.

BJP era Modi has therefore done the two things necessary to win in modern politics, making people feel rich and making them feel seen. This is why even the Economist, hardly a fan, admits he is the world’s most popular leader. You can use this dyad to explain the success or failure of various political parties in the West. The Tories are hated because they have made people feel neither rich nor seen. Brexit was popular because it promised both (and Tory failure is compounded by the post-Boris feeling of Brexit betrayal). Joe Biden is unpopular because, while America’s economic indicators are objectively good, they do not feel good to voters, and he does not make anyone feel seen except self-conscious neoliberals like Matthew Yglesias or Noah Smith. These two and the sort they represent may support policies that are popular objectively, but they do so from a nonrepresentative rationalist perspective and are highly unusual in terms of where their politically emotive triggers lie. Dark Brandon anybody?

Another interesting thing about Modi that helps his popularity is that he exemplifies the model of the celibate political leader who dedicates himself to a cause. While technically married at 18 he almost immediately abandoned his wife for a life, publicly at least, of chastity and political activism. This image is of course echoed in the life of Gandhi, who though already married and a father of four, took a vow of chastity in 1906 aged 38, and maintained the image of a chaste politico-spiritual leader throughout his subsequent political career. This idea of the celibate priestly political leader seems quite unique to India. Europe of course had its monks, but they did not get involved in political leadership. Though there is one Western political leader who maintained a similar public image, Adolf Hitler, another interesting parallel between Nazi Germany and India in addition to the Swastika and Aryanism.

Right-wing parties represent the core identity, left-wing parties represent a coalition of the fringes

In any culturally and ethnically divided society one of the political dynamics that you see is one party representing the core identity of a nation vs one representing a coalition of its fringe identities. In the US from the civil war to the 1960s the Republicans represented the core (Northern and Western WASPs, i.e. the literal and spiritual descendants of those who had won the civil war) and the Democrats represented the fringes (Southerners and ‘white ethnics’ like Irish, Italians and Jews, i.e. the New Deal coalition). In the 60s and 70s white Southerners and some of the white ethnics switched to the Republicans, who came over the next few decades to represent the new core identity: white Christians, while the fringe identities of social liberals, Jews, blacks and non-white immigrants were represented by the Democrats. ‘Coalitions of the fringes’ (in Steve Sailer’s terminology) tend to have little that bind them together beyond opposition to the core identity.

The same pattern increasingly holds in Britain as class politics gives way to identity politics. Broadly speaking identity-wise, the Conservatives represent the English (symbolically - in reality they betray them at every turn), while Labour represent the social left (who are broadly anti-English identity in their worldview), immigrants and ethnic minorities. Of course class and interest-based politics still matters too but identity-wise this broad pattern holds. As with America, those who run the Labour party have little in common with their electoral footsoldiers, as we are seeing over the current Gaza protests.

India increasingly displays the same pattern. In India the core identity is Hindu by religion (80% of the population), Hindi (or more broadly Indo-Aryan) by language, and within the four varnas (i.e. excluding the scheduled castes, the administrative term for Dalits). Broadly speaking, the BJP represents this core identity, while Congress represents the peripheral ones: the south (where Dravidian languages are spoken, Muslims and Christians, elite social liberals who control the party, and scheduled castes.

Lessons

India as a country is clearly in a class of its own and the rise of Hindu nationalism to hegemony has taken place in a period of national development which any Western country went through long ago. However there are several general lessons that can be learned from all this.

One is that even if the overall political situation and official political formula you live under is against you, there is always something useful you can do in terms of movement building. It took nearly 100 years from the founding of the RSS for its ideology to be implemented by the state.

Another is that even in a diverse society where diversity is held up as a national value, it is eminently possible to raise the traditional identity of a country above all others and identify it with the state: you just need enough people to care and willingness to work hard for the goal. Of course there will be opposition and protests, as for example there were against the new Indian citizenship laws in 2019. But protests do not have to be fatal to political rule.

A third is that success and political expediency trumps all things. Modi was a pariah in the West in the early 2000s and was banned from entering much of it due to his response to the 2002 Gujarat riots. Now he is feted and courted as a counterweight to China, his opposition to all values the West purports to hold dear ignored. The lesson here is, if you win and people need you, you will be accepted.

Other articles you may like…

Dubai, the contingency of economic development, and the Great Man theory of history

The unlikelihood of Dubai

I don’t mind Modi, he’s a kewl guy, but he doesn’t seem any more conservative than guys in the west. As far as I know, he is not a “caste affirmer” and doesn’t campaign heavily on reducing India’s extensive system of affirmative action. Many Indian conservatives have resorted to denying caste as an “Anglo Imperial construct” despite genetic evidence demonstrating that Caste has existed and been taken very seriously since at least the Gupta Empire, and probably existed in some capacity since the Aryans arrived (another thing Hindutva types like to claim is a British lie, despite being very well-backed).

His attitude towards Islam is good and all, but it is not worthy of him being hailed as Kalki himself (I have seen some actually do this)

Priestly and celibate are actually two completely unrelated things in Indian culture. Priests have always been allowed and even encouraged to marry in Hindu societies. And celibacy is one of the lifelong vows that anyone, from any background, can take in service to a specific deity or cause. There are actually a dozen or more local leaders in the BJP that have taken such vows. I am inclined to believe that they do actually follow this lifestyle because if they didn’t the opposition party would be screaming about it from the rooftops. A vow of celibacy is of course a very simple and highly effective way to lend credence to your political agenda but that’s not enough of a reason to doubt the sincerity of it.

One thing that I don’t see enough people talk about is how genuinely progressive the BJP has been in its approach. Their leaders, even the geriatric ones, don’t hesitate to use and integrate the latest technology in any way they can. They have come up with some of the most effective tools for money transfer and online portals for all kinds of administration, and recently they are rolling out AI tools for real time audio translation and softwares for self-directed learning. They have heavily subsidized internet access and mobile connectivity in the past and now they are promoting startup ecosystems. One of the most refreshing things is when the party leaders and parliamentarians can get onto podcasts and openly discuss politics and their work for several hours at a time- it clearly shows the level of intelligence and competence of any politician to see them be spontaneous and engaged. They seem to be embracing all change while the opposition is stuck in the past, and even the most apolitical, simple-minded and disengaged person can clearly see the difference.