On the Folk Beliefs of the Upper Normie: “National identity is just about citizenship”

Part 1 of a series.

This is the first in a series on ‘The Folk Beliefs of the Upper Normie’. Future ones will look at topics like the idea of nations as modern inventions, and the idea that Europe was a backwater before colonialism.

A version of this article was originally published in The Critic on the 23rd March.

I have always liked the concept of the upper normie. An upper normie is someone who holds conventional mainstream opinions but is a bit more intelligent than the average and thus considers themselves to be more sophisticated than the normal normies. Common examples of the upper-normie worldview in Britain are the #FBPE movement, James O’Brien fans and the Rest is Politics listeners.

Because the upper normie is more conventionally-minded than they think they are, they tend to believe the conventional high-status wisdom of their age. Today this looks like a mix of the establishment liberalism that became hegemonic in the West after WW2 (which N. S. Lyons has called the open society consensus) combined with, depending on how left-wing the upper normie is, elements from postcolonialism and wokeness (or cultural socialism as Eric Kaufmann calls it).

Today, with the Trump administration and the fraying of the establishment liberal consensus, there is an idea that we are in the midst of a vibe shift. More ambitiously, as N.S. Lyons puts it above, we are seeing the end of the long 20th century and the birth of a new world order, based on the return of the “strong gods” which were repressed by establishment liberalism. I believe that this shift he describes is indeed happening, yet the conventional wisdom persists. While the White House - and elements of the tech right - are trying to replace the old consensus, it will take time for the consensus and thus for the upper-normie worldview to change.

Folk Beliefs

Every society has its folk beliefs: sayings and stories about the world that are widely held yet not grounded in fact, and I have come to think of much of the upper-normie worldview as a collection of these folk beliefs. These are not the old sayings about health and wealth that might be passed down via your grandmother, but somewhat muddled and simplistic ideas about history, nationhood, economics, colonialism, race etc. that originated from academia, the media, the cultural industries, governments and NGOs over the long 20th century.

As an example, one way upper-normie folk beliefs manifest is that their favourite, and in many cases only historical analogy is to the Nazis: in the establishment liberal worldview the Nazis serve as the representation of what is bad, while ‘not the Nazis’ represents what is good. Thus topics as varied as Putin (‘Putler’), Hamas (‘worse than the Nazis’), Elon Musk (‘Swasticar’) or pictures of happy blond families (‘like something out of Nazi Germany’) are not understood on their own terms but because they are deemed to be reminiscent of the Nazis.

However the folk beliefs which I am particularly interested in are those that make specific historical claims in the service of a liberal or cultural socialist worldview relating to nationhood, ethnicity, western economic development and colonialism. These often originate in academia but generally simplify or distort the original work, or are highly selective of it. Thus in a very upper-normie way, they purport to be the smart, expert view, while actually being far from this.

The specific beliefs I want to look at include “national identity is just about citizenship”, “nations are modern inventions” and “Europe was a backwater before colonialism.” The first of these I am going to discuss here, and the others in future articles.

“National Identity is just about citizenship”

This folk belief holds that national identity is purely a matter of legal citizenship, and that beyond this it can only consist of an adherence to vague liberal universal values (e.g the idea of “British values”) or twee national characteristics like queuing and drinking tea. I discussed liberal universalist patriotism previously in Liberal patriots and most Christian Kings, and the prosaic conception of culture in Against the ‘ethnic food festival’ conception of culture.

Recently this belief has held the status of the Current Thing, kicked off by the question of whether or not Rishi Sunak (and subsequently Suella Braverman) is English, to which many commentators responded with somewhat performative outrage that such a question would even be considered - Owen Jones providing a good example here:

Jones is displaying the characteristic obtuseness of the upper normie here, in contending that the answer to a complex question is actually so obvious that any alternative view can only be treated with derision. This style of take on substantive questions is characteristic of the upper-normie view on many questions. An example is the classic Redditism “just be a decent human being” as the only answer to moral issues, as if the idea that there might be something more to morality than Millian liberalism is incomprehensible.

The corollary to the ‘civic-only’ conception of national identity is that, against all evidence of lived experience, there can be no ethnic identity separate from the civic one, as epitomised in this other recent tweet on the ‘who is English’ controversy:

Beliefs like this are only really possible to hold either as a polite fiction or by those who are either highly unreflective or highly mendacious (or both). Unreflective members of the ethnic majority (i.e. the upper normie) are particularly prone to holding them due to the common ‘the fish can’t see the water it swims in’ psychological tendency they fall prey to. For ethnic minorities in supposedly civic nationalist countries like England or France it is much more instinctively obvious that there is a concept of ethnic Englishness or Frenchness distinct from the national one, though those of them who fall into the highly mendacious category can still deny it for self-interested or political reasons.

Therefore I don’t feel there’s any need to spend much time proving that the civic-only conception of national identity does not reflect how things are in reality, or how people think about it if they truly reflect on the question. There have been a few good articles recently addressing this, e.g. Chris Bayliss’s What does it mean to be English?, which discusses the widespread reluctance today to concede that there is an English ethnicity and the reasons this came to be so. Instead, here I want to look at the intellectual history of the civic nationalist idea and how it came to predominate as upper-normie conventional wisdom.

The Idea of Civic Nationalism

Many have observed that a division in national identity arose during the age of nationalism from the late 18th century onwards, between the so-called civic form of Western Europe and its American offshoots, and the ethnic form of Central and Eastern Europe. The argument goes that national identity in Western countries like Britain, France and the US was defined by citizenship of the state and was imbued with the progressive and egalitarian political ideals of the age. In Central and Eastern Europe however, national identity was based on ethnic communities deriving from a romantic connection to the medieval past, and was a force that was oppositional to the existing states and empires of the day (as in the Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman empires).

Many writers have tried to define what makes a nation over the centuries, but the explicit civic/ethnic distinction originates with Hans Kohn’s 1944 book The Idea of Nationalism: A Study in Its Origins and Background, an idea which became highly influential in subsequent decades. The distinction makes sense on a surface level for the nationalism of the late 18th to early 20th centuries, especially relating to its two primary archetypes of France and Germany. The nationalism of post-revolutionary France had the state and citizenship as its object and promoted the same status as ‘citizen’ for all who held it. The German nationalism of the same period developed in the absence of a single, overarching German state and was defined by German language and culture, distinguishing the Germans from the other peoples that surrounded and lived amongst them.

However the civic/ethnic distinction is mostly a false dichotomy. ‘Civic nations’ grew around strong ethnic cores that anchored the state, even if this fact was not emphasised explicitly (and often in fact it was emphasised explicitly). It was this underlying ethnic identity that allowed them to build a civic identity which outlying minority groups could assimilate into. ‘Ethnic nations’ looked to the state just as civic nations did, it was just that in most cases the state they envisaged did not currently exist, therefore their national movements had to use non-state markers of identity or the memory of their historical states or kingdoms. The states they aspired to would then, ideally, assimilate their remaining minorities just as was happening in the civic nations. A good book which deals in depth with these processes is Azar Gat’s Nations: The Long History and Deep Roots of Political Ethnicity and Nationalism - but I’ll briefly talk about the development of a few supposedly civic nations.

Civic Nations are also Ethnic Nations

Post-revolutionary France was the archetypal civic nation, but the French state and people developed over a period of hundreds of years before this. We can observe a 500-year process where the kings of France, beginning with Philip II in the late 12th century (the first to style himself King of France, not King of the Franks), steadily expanded their own power, constructing the apparatus of the future state in the process.

It is often emphasised that pre-revolutionary France was made up of many non-French speaking areas with their own identities, laws, and fiscal and political privileges, including Brittany, the Germanic provinces in the east (which became Alsace-Lorraine), and the Occitan-speaking ones in the south. The basis of the kingdom though was the large area of north-central France centered on Paris that contained the oldest provinces. The core French people developed here, a fusion of Franks and Gallo-Romans speaking the langues d'oïl which became the modern French language. You can see from maps of pre-revolutionary fiscal zones and the Parlements that there was a distinction made between core France and the outlying ‘provinces considered foreign’ which correlates quite well with where the langues d'oïl were spoken. Based on this core region of political and ethnic Frenchness, from the revolution onwards and into the 19th and 20th centuries the French state carried out a highly successful assimilative project of these outlying regions.

The development of England as a national state was well established by the 10th century, forged under pressure from the invading Danes. By the late medieval period, once the long process of assimilation of the Normans was complete, England had become one of the most centralised and ethnically homogenous kingdoms in Europe. The formation of Britain by the Acts of Union of 1707 joined England to Scotland, another long established state centered on the lowland Scots, creating a more civic national identity, but one still defined by specific peoples with a shared language family and protestant religion.

The idea that the US’s identity has always been one of a nation of immigrants is an invention of the 1960s. Before this, the country’s identity had been defined not by Ellis Island, but chiefly by its Anglo-Protestant heritage, by Jamestown, Plymouth Rock, the revolutionary and civil wars and the winning of the west. The Statue of Liberty stood for the political liberty achieved in these wars, not for the ‘huddled masses yearning to breathe free’ that it later came to represent. Thomas Jefferson, for example, saw America as continuing the Anglo-Saxon tradition of freedom, while Founding Father John Jay wrote in 1787:

“Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country, to one united people, a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs”.

Indeed a large majority of white Americans were of British origin at the time of the revolution and for a long time after. Eric Kaufmann’s The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America is a good source to read about this.

In the late 19th and early 20th century too, civic nations were also ethnic nations. In Britain and America this was the age of Victorian Anglo-Saxonism, when historians straightforwardly talked of the Anglo-Saxon race and traced the origins of both nations back to this original ethnic stock. Since the Immigration Act of 1924 the USA had explicitly employed the national origins formula with the goal of maintaining its ethnic identity. In France, the revolution had been seen in one sense as having finally released the Gauls from the oppression of the Franks (analogous to the idea of the Norman yoke in England). As Emmanuel Sieyès, leading political theorist of the French revolution, wrote in his 1789 pamphlet What is the Third Estate:

“Why not, after all, send back to the Franconian forests all those families still affecting the mad claim to have been born of a race of conquerors and to be heirs to rights of conquest? Thus purged, the Nation might, I imagine, find some consolation in discovering that it is made up of no more than the descendants of the Gauls and Romans.”

The popular 19th-century school textbook by Ernest Lavisse on the history of France continued this emphasis when it recounted that:

“The Romans who came established themselves in Gaul in small numbers. The Franks were not numerous either, Clovis only had a few thousand with him. The basis of our population has thus remained Gaulish. The Gauls are our ancestors”.

The Postwar Idea of Purely Civic National Identity

In the second half of the 20th century the civic-only conception of national identity triumphed in Europe and America, at least officially. While Nazi Germany and WW2 did a lot to discredit ethnic forms of nationalism, the transformation was not a direct reaction to the war, which after all was viewed at the time as a victory for the still both civic-and-ethnic English-speaking peoples. In 1949 Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers in Japan, General Douglas Macarthur, while clearly seeming increasingly like a man of a fading age, could still be reported as saying that the Pacific was now an “Anglo-Saxon lake.”

The real transformation only took place from the 1960s onwards, when a new moral paradigm took root in the Western world that interpreted its own history as fundamentally negative. This was symbolised by the new rise to prominence of the Holocaust as the ultimate lesson of WW2, rather than the fight against tyranny as had been emphasised at the time. The Holocaust, and fascism more generally, were now cast in works such as Adorno’s highly influential The Authoritarian Personality as being caused by newly-pathologised tendencies in the population such as ‘ethnocentrism’. The only non-negative things that could be salvaged from Western history were abstract anti-strong god principles like tolerance, liberalism and universal human rights, and it was these that became the basis of the new official forms of purely civic national identity.

In Germany, even after 1945 the traditional ethnic model of citizenship based on descent, not residence, persisted for some decades. Initially the Turkish and other foreign guest workers of the 1950s and 1960s were not granted German citizenship and nor were their German-born children. This distinction broke down, as Christian Joppke makes clear in his 1998 book Immigration and the Nation State, not via the democratic political process but due to a succession of court cases in the Constitutional Court that ruled against government policies on immigration. (This is one of many historical examples where the cause of establishment liberalism was advanced via the legal process against the intentions of the executive). The old system of nationality law was finally ended in the 90s when naturalisation of immigrants and dual nationality became permitted and jus soli was introduced for children of long-term resident immigrants. The traditional German conception of identity was thus replaced by the idea of ‘constitutional patriotism’ promoted by thinkers like Dolf Sternberger and Jürgen Habermas.

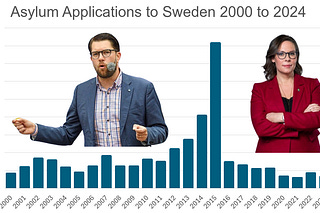

In the 60s, the USA saw its traditional identity that had been defined by the original Anglo settlers, the revolution and the westward expansion transformed to the ‘nation of immigrants’, symbolically initiated by the 1958 ADL-sponsored book “A Nation of Immigrants”, written by John F. Kennedy. The 1965 Immigration Act removed the national origins formula, paving the way - against the expectations of the congressmen who voted for it - for large-scale immigration from non-European countries. In countries like Britain and France, where the civic conception had long been balanced by a sense of ethnic identity, the latter was de-emphasised and banished from polite discourse.

‘Purely Civic’ Nations Cannot Ignore Ethnic Realities

As a result of these historical developments the more balanced idea of national identity as a mix of civic and ethnic elements has been lost. We now have a widespread belief that there are two distinct forms: the good, inclusive, civic sort that we supposedly have, and the bad, exclusive, ethnic sort belonging to the past. It is this belief that is at the root of the upper-normie worldview on the question.

In a sense the advocates of purely civic nationalism have started to believe their own propaganda. In reality, civic nationalism is a kind of a fiction that allows for the tolerance of minorities and, if things go well, the forging of a new core ethnicity out of old and new elements. It has never really meant, and does not mean today, that national identity is purely a civic matter divorced from ethnicity, nor that nations do not have a core Staatsvolk or dominant ethnicity.

Civic nationalism can work successfully but only if the underlying core ethnic identity of a country is not threatened too much. In the US, despite recent political conflict over the issue, the predominantly Hispanic and Asian immigration of recent decades has proved more compatible with the historic core white ethnic majority than immigration to European countries over the same period has. Its model will not necessarily continue to work forever, but the political discontent in Europe shows far more starkly what happens when the civic idea is taken too literally and ethnic realities are ignored. The error that the upper-normie civic nationalists make is to assume that the civic model will necessarily succeed regardless of the underlying ethnic situation. But this is little more than an article of faith, or folk belief, coming into increasing conflict with reality.