Prospects for a 'fund the NHS, hang the paedos' party in the UK

Since the demise of Boris Johnson’s premiership and the Tories’ polling collapse, various calls to replace the seemingly played-out party have been made, e.g. by such figures as Dominic Cummings and Nigel Farage. While the Sunak premiership does not provide quite the same electoral opportunity as Truss’s crazed and electorally catastrophic libertarianism did, the party is still trailing Labour massively in the polls, and the base assumption must be that Sunak’s government will be little different from the Tory governments of the past decade; i.e. fighting talk on immigration and a thriving economy that works for all, but a reality of continuing sky high net migration rates and a stagnating unequal economy oriented towards keeping house prices high.

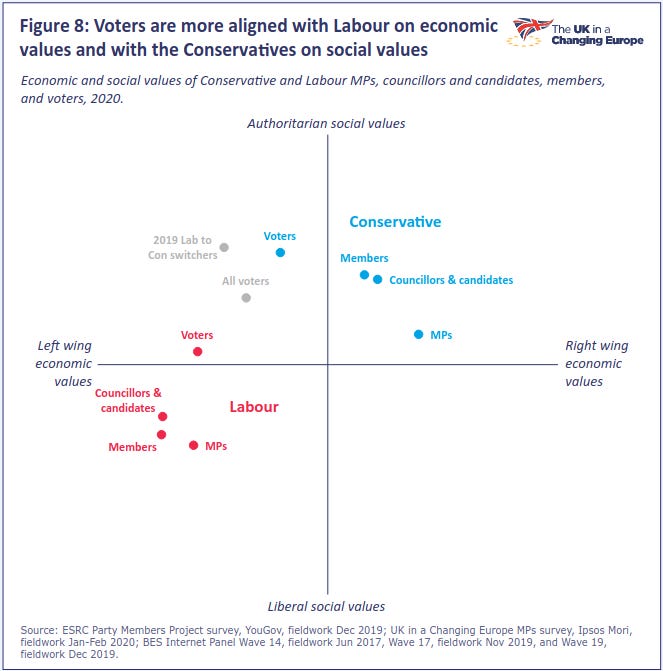

As has been pointed out in many places over the last few years, the real centre ground and ‘gap in the market’ in British politics (and probably politics in all countries) is economically left-wing and socially conservative, or ‘fund the NHS, hang the paedos’ (referred to hereafter as FNHP). However, among elites, or more precisely the sorts of people most likely to staff, fund and promote a successful political party, these combination of values are far less common, while the opposing economically and socially liberal political compass quadrant is overrepresented. This contrast explains the unpopular economic libertarianism of the Tories, the similarly unpopular woke activism of Labour, and the fitful delusional efforts by the least perceptive liberal bubble-dwellers to form new ‘centrist’ parties like Change UK. After all, the average Conservative voter is closer to the average Labour MP on economic values than they are to the average Conservative MP, while the average Labour voter is closer to the average Conservative MP on social values than they are to the average Labour MP. So an opportunity exists, at least in terms of public opinion, for a challenger party.

Does such a party exist in the UK?

The most prominent relevant challenger party at the moment, at least on the ‘hang the paedos’ metric, is Reform UK, who are currently polling at 7%, quite high for a party with no real media presence, and since Britain left the EU no hook to hang their policy agenda on. However with their pledge to become a low tax economy, they’ll be perceived more as ‘hang the NHS’ than fund it. While there are voters who find the Tories too economically left wing, they are few, and thus without the hook of Brexit to hang on, Reform UK does not seem to have a policy package that means it could grow its support base. Their relative popularity is largely down to their previous incarnation as the Farage-led Brexit party, which got nearly 650,000 votes at the 2019 election when Brexit was still a live issue.

The party that is closest to the FNHP ideal is the SDP, with their pledges to drastically cut migration and to withdraw from international agreements that deny UK border sovereignty, while also increasing the top rate of tax and increasing the share of national income spent on the NHS. However they have a far lower public presence than Reform UK, getting only 3,295 votes at the 2019 election, and having only a couple of council seats.

Does such a party exist anywhere?

In France, Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party got 41% of the second round vote in the 2021 election. This is as pure FNHP as you can get, with the party advocating a highly restrictive immigration policy in combination with economic protectionism, and Le Pen even pledging earlier this year to hold a referendum on reinstating the death penalty.

Why does it exist in France but not the UK? The French elite seem generally as hostile as the British elite would be to an equivalent party, with the National Rally having to take loans from Russian and Hungarian banks because French ones will not lend it money. On the demand side, the French electorate is more economically protectionist, and France has greater problems with the integration of immigrants, i.e. the electorate is even more FNHP friendly than the UK one is. However the most important reason is likely to do with the electoral system, the French two-round system allows for the growth of smaller parties more than the British FPTP one does.

Strategy for an FNHP party in the British system

Any FNHP party therefore faces a structural disadvantage due to the British electoral system. Even if its ideals and policy programme are attractive, this is not enough to counteract the fear among voters of a wasted vote. The best strategy for a minor party to mitigate this disadvantage is to advocate for policies that the two major ones cannot or will not: otherwise they can just steal the policies and render the minor party redundant. We have seen this successful strategy from UKIP (exiting the EU), the SNP (exiting the UK), the Lib Dems in recent years (rejoining the EU) and the Greens (focusing primarily on the environment). With these kind of policies, voters may still choose the minor party if they care about the issue enough and think neither major party is going to do anything about it.

Despite immigration concern dropping since Brexit, there are still large numbers who want immigration reduced, especially among leave voters, and there are no signs that Labour or the Tories are intending to reduce it (except for the channel boats issue which is only a small percentage of the whole). Therefore immigration seems the best option for a ‘hook’ policy that would draw voters in without being then immediately being taken over by the main parties.

The SDP already has this hook in its policy programme, with pledges to withdraw from the 1951 UN refugee convention, reduce net migration to 50,000 a year, promote a generation long ‘mass immigration pause’, and decline all asylum applications via breaches of the UK border. They have other popular policies too (on the ‘fund the NHS side’) but none are important enough to draw voters in and differentiate themselves from the main parties. The pledge to renationalise the railways comes close; this has majority support from the public, but it seems like something that Labour could switch to without too much trouble, considering there is strong support within the party for it and the leadership keep u-turning on the issue.

The SDP’s ‘FN’-side policies would function more to solidify its support than attract it initially, i.e. to persuade a voter attracted by its pledges on immigration that the party had more of their interests at heart than just this one and was a genuine concern worthy of support. If the party did then manage to gain a significant electoral foothold, these policies would then become more important in the battle to persuade voters who do not have immigration as a primary concern, but do not mind an anti-immigration policy, to vote for it. Of course the progressive-activists who see immigration as a sacred value would never vote for a party like this, but these people are a small and geographically concentrated proportion of the population, their electoral power comes from their position guiding the much broader-church Labour party, as well as less directly through their control of the culture.

In short then, for the SDP or any hypothetical FNHP party, the best strategy now is to focus primarily on immigration, but to give enough airtime to its other popular ‘FN’ policies to solidify support and make the party seem like a real contender, not a single-issue pressure group.