“The NHS and social care would collapse without immigration”: a European comparison

Those who make claims of inevitable collapse never look at our nearest neighbours

A version of this article was previously published in UnHerd on the 10th March.

One characteristic claim made by those who don’t think very deeply about our immigration system is that current levels must continue because the NHS, or the care system, would otherwise collapse. This argument ignores actual policy and history and is generally made in the same way whatever current immigration levels actually are, even when they have risen to unprecedented levels as they have in recent years. As an argument it is also highly parochial, as British commentary on the NHS so often is: those who make it never think to compare Britain with the situation of our closest neighbours and to ask why we are so much more reliant on this form of immigration than they are.

The situation in Britain

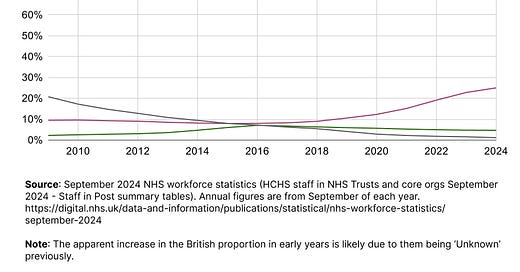

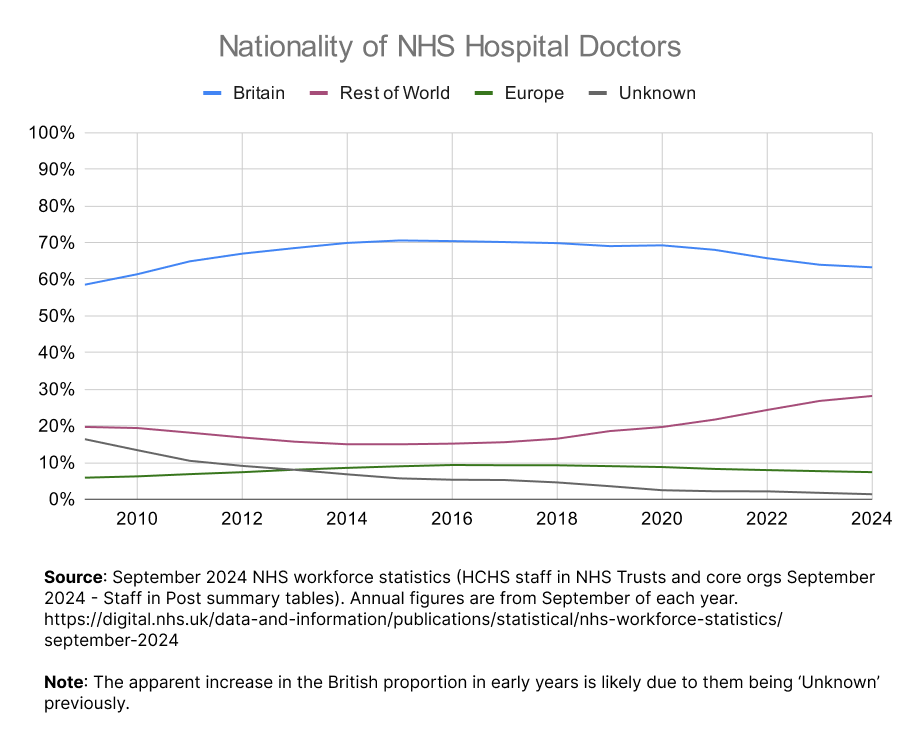

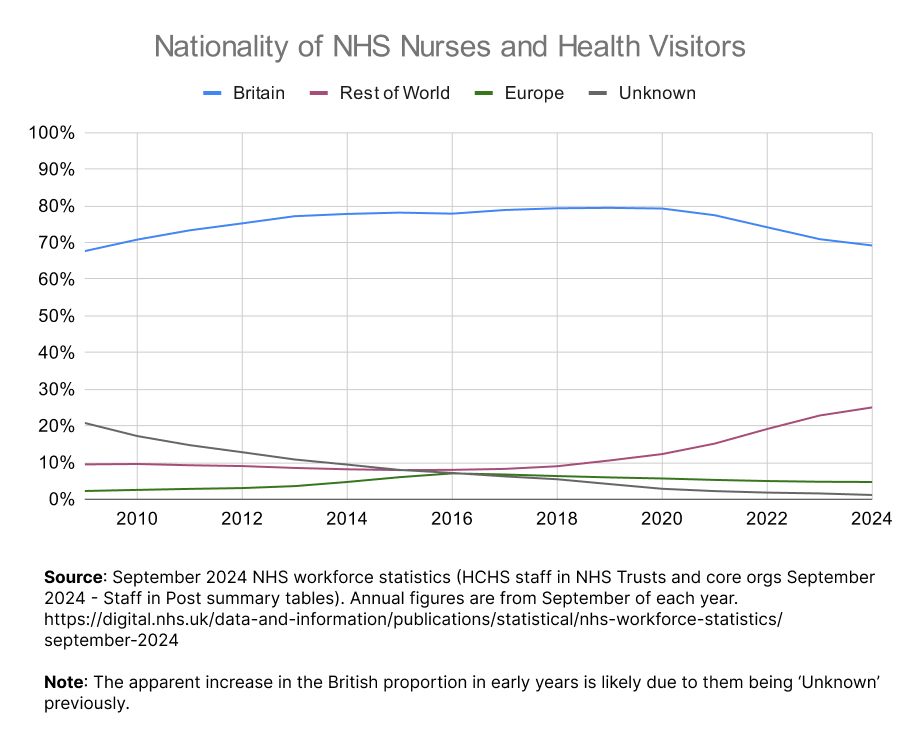

The NHS is indeed highly reliant on immigration. As of September 2024, 36% of its 156,000 hospital doctors and 30% of its 400,000 nurses are non-UK nationals. Our high rate of foreign medical staff is hardly a new trend, but neither is it some constant law of nature divorced from political decisions. The figures from recent years have been unprecedented: what happened over the last 15 years was a slower level of change until 2020, then an accelerated one once the government introduced the Health and Care visa in August 2020. This is when the Boriswave really got going.

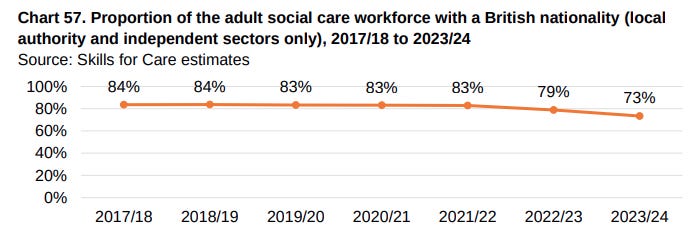

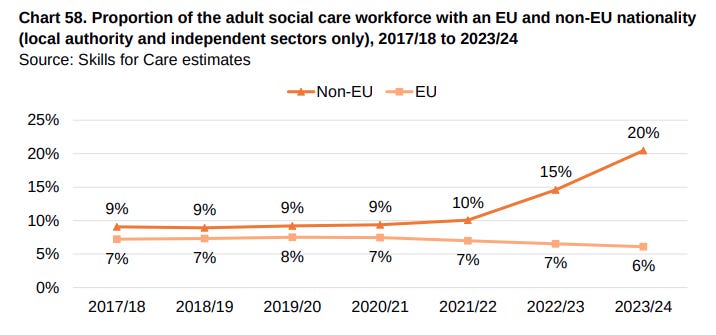

The change in adult social care is even more marked. The balance between British, EU and non-EU staff had been relatively static until 2022/23, when it started to shift strongly towards non-EU workers due to the addition of care workers and home carers to the Health and Care visa in February 2022.

Much has already been written about the failures of the Boriswave. Its huge future fiscal costs due to the low wages of the visa holders, the large number of accompanying dependants it initially permitted, the lack of an age limit, and more broadly the acceleration of the already fast-advancing demographic transformation of Britain. But here I want to talk about the question of inevitability or system collapse which so often accompanies discussion of this topic. Importing foreign healthcare workers is a growing trend globally, but why are we so much more extreme than other European countries?

European comparisons

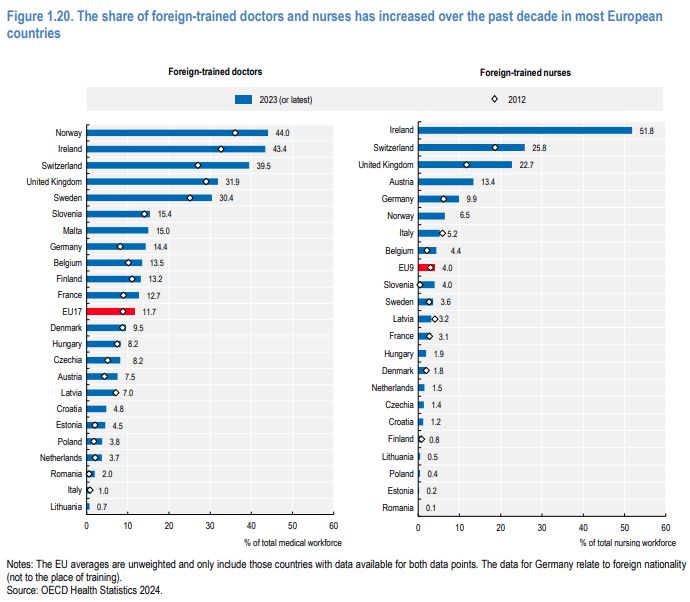

If we look at the OECD’s statistics for 2024, we can see that Britain, along with Ireland, is a massive outlier in the percentage of foreign-trained doctors and nurses. Norway, Sweden and Switzerland appear to be outliers too but their situation is not really comparable. In Norway and Sweden large numbers of foreign-trained medical staff are native students who studied for their medical qualifications abroad before returning home, while in Switzerland nearly all the foreign-trained doctors and nurses come from neighbouring countries. Other European countries range from having half the UK rates of foreign doctors and nurses (e.g. Germany) down to a third or less (e.g. France, Italy and Denmark).

So why is this? We often hear of the large numbers of British (and Irish) doctors moving abroad, requiring us to replace them from other countries, but the numbers are not as great as are often suggested. Britain trains around 9,500 graduate doctors per year, of which in 2022 1,403 left to practise abroad (around 15%), while data from 2012-2017 indicates that 43% of those who do work abroad later return, generally within three years. This indicates that less than 10% of British graduate doctors are lost to the NHS over the long term.

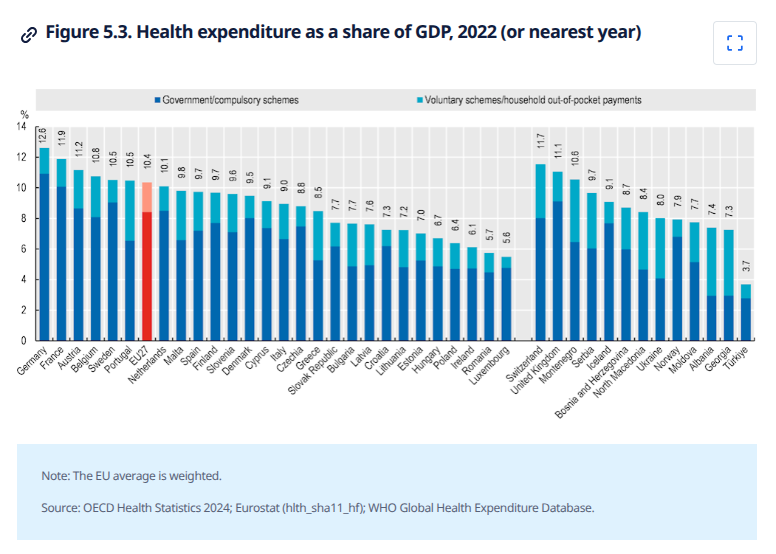

Doctors leaving for abroad then cannot fully explain the high rates of foreign trained doctors in Britain and Ireland. Given that comparable European countries like France can run a health service that is by many accounts superior to the NHS with far lower rates of foreign workers, the way we do things is evidently not the only choice available. Neither is it the case that Britain gets its healthcare on the cheap via importing lower paid medical staff; looking at the percentage of their GDP different countries spend on healthcare, Britain, though spending a bit less than Germany or France, spends more than most comparable European countries.

International comparisons for care workers are harder to find, though even in the pre-Boriswave days of 2019, Britain was one of the few European countries along with Luxembourg, Malta, Ireland and Austria where the share of migrants among care workers exceeded 10%.

Given these international comparisons, the reality seems likely to be that Britain and other English speaking countries simply can recruit from abroad due to the international availability of English-speaking workers, rather than that they must do so to the extent that they do. Policy changes though can still make a massive difference to the numbers and to the outcomes, fiscal and otherwise. Indeed in spring 2024 the Conservatives under Rishi Sunak belatedly restricted the ability of holders of Health and Care visas to bring dependants. This change, coupled with increased Home Office scrutiny, led to an 81% decrease in visas granted to main applicants in 2024 vs 2023. No one today thinks that the NHS or the care system is functioning well exactly, but neither are they ‘collapsing’ in a way that they were not collapsing in 2023, as a result of this large decrease in visa grants.

I am not trying to argue that these are easy issues to solve: increasing reliance on foreign workers for health and care work is rooted in ageing populations and resulting workforce and financial constraints. It is an increasing trend worldwide, but as with many aspects of immigration, Britain is an extreme case and has handled it especially poorly particularly over the last few years. In this context, lazy claims of inevitability and collapse are not just evidence of a serious lack of knowledge and imagination, but are especially pernicious.

Other articles you may be interested in: